Anti-Rejection Medications: Analysis of Reported Errors

In follow-up to several recent reports of incidents involving medications used to prevent organ rejection, a multi-incident analysis was conducted. The analysis identified system vulnerabilities, and selected system safeguards to improve medication safety.

INTRODUCTION

Patients who have undergone organ transplant require multiple medications to prevent organ rejection. Therapeutic management aims to suppress the immune response that can result in damage or loss of a transplanted organ while also ensuring there is a sufficient immune response to be able to fight infections.1 In follow-up to several recent reports of incidents involving medications used to prevent organ rejection, a multi-incident analysis was conducted. The analysis identified system vulnerabilities, and selected system safeguards to improve medication safety.

METHODOLOGY

Reports of incidents with anti-rejection medications were extracted from 3 ISMP Canada reporting databases (Individual Practitioner Reporting, National Incident Data Repository for Community Pharmacies, and Consumer Reporting) and the Canadian Institute for Health Information’s (CIHI) National System for Incident Reporting (NSIR) database* for the period August 2016 to July 2021. The search terms used to extract the incidents included “transplant”, “rejection”, “graft”, “host”, “donor”, “recipient”, and “organ”, as well as the generic and brand names of medications (immunosuppressants and corticosteroids for systemic use) prescribed to prevent rejection after a transplant. Incidents were excluded if it was not clear that the patient was taking these medications to prevent rejection of a grafted organ.

QUANTITATIVE FINDINGS

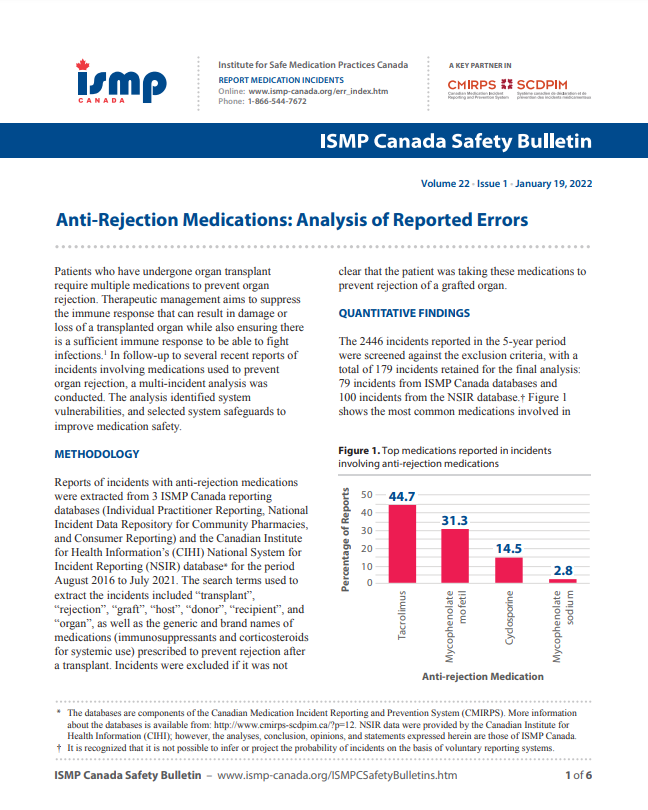

The 2446 incidents reported in the 5-year period were screened against the exclusion criteria, with a total of 179 incidents retained for the final analysis: 79 incidents from ISMP Canada databases and 100 incidents from the NSIR database.† Figure 1 shows the most common medications involved in these incidents, while Figure 2 breaks down the reported outcomes. Tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and cyclosporine were the most frequently mentioned medications.

The reports included in the analysis generally did not capture resultant longer-term harm (e.g., rejection of the transplanted organ); however, several did specify acute organ dysfunction as an outcome. The inclusion of near-miss and no-harm incidents in the analysis offered an opportunity to proactively identify successful processes, as well as areas for system improvements.

Figure 1. Top medications reported in incidents involving anti-rejection medications

Figure 2. Outcomes reported for incidents involving anti-rejection medications

QUALITATIVE ANALYSIS

Three themes and several subthemes identified through the analysis are presented in Figure 3 and discussed below.

Figure 3. Themes and subthemes identified in the qualitative analysis

Theme: Formulation Mix-Ups

Health care professionals working outside the field of organ transplantation may have limited experience with anti-rejection medications. Knowledge gaps related to the differences in medication names, salt compounds, and formulations led to mix-ups between noninterchangeable products. Errors most often occurred between immediate-release and extended-release tacrolimus products; a previous publication provides an example.2 Mix-ups between mycophenolate mofetil and mycophenolate sodium were also reported.

- Immediate- and extended-release tacrolimus: Prograf is an immediate-release formulation (dosed twice daily) whereas Advagraf is an extended-release formulation (dosed once daily). Both are available as 0.5 mg, 1 mg, and 5 mg and this contributed to mix-up errors.2,3 A prolongedrelease formulation of tacrolimus (brand name Envarsus PA) is dosed once daily and is also available as 1 mg, so there is a risk of mix-up between all formulations of tacrolimus. A recent report described the inadvertent dispensing of Envarsus PA instead of a prescribed immediate-release product. Errors with these medications can lead to adverse effects including increased susceptibility to infections or organ rejection.4

Incident Example

An immediate-release tacrolimus product was prescribed for a patient, but an extended-release tacrolimus product was dispensed. Routine blood work revealed a tacrolimus level substantially higher than the therapeutic range. By the time the error was discovered, a chronic infection had developed.

![]()

TIP: Include both brand and generic names during each stage of the medication-use process (e.g., prescribing, dispensing).

Theme: Complexity of Care

Caring for patients who have recently undergone an organ transplant is complex and includes the need for various new medications and associated drug monitoring. The following subthemes reflect this complexity:

- Therapeutic drug monitoring: Cyclosporine and tacrolimus are both commonly used immunosuppressants with a narrow therapeutic index. Patients taking these medications must undergo lab work to monitor drug levels, which are used to determine subsequent doses.1,4 Several reports described doses not being administered on time because of the need for blood draws or the wait for lab results. There were also errors related to the frequent dose changes that are often required to maintain targeted blood levels of these medications. Contributing factors included a lack of clear communication among members of the care team, including patients/family.

![]()

TIP: Where possible, incorporate electronic notification of required blood work and reporting of results.5 This information can also be noted on the written prescription to communicate with community care providers.

- Preparation and administration of intravenous (IV) medications: After patients have received a transplant and before they can tolerate oral agents, anti-rejection medications are administered by IV infusion. Factors contributing to errors with IV medication administration, as cited by reporters, included the complex processes associated with preparing these products, a lack of independent double checks, disorganization in the storage space, and transcription errors on the medication administration record.

- Multiple medication regimen: After a transplant, patients must take specific doses of multiple medications, at specific times, to prevent organ rejection.1 Several incidents described administration of partial doses and mix-ups between administration times. Drug interactions between an anti-rejection agent and other medications were also reported. In many instances, the pharmacy team identified the drug interactions and adjusted the medication regimens accordingly.

![]()

TIP: Implement independent double checks on these high-alert medications at vulnerable points in the medication-use system.

Incident Example

A patient’s blood was drawn for determination of tacrolimus level, but the results were not received by the pharmacy before the next dose was due. This delay prevented a timely dose adjustment.

Theme: Coordination of Care

Seamless and timely transfer of key patient information among multiple health care professionals, both within the hospital and in the community, is needed to prevent medication errors; this is especially important in complex situations such as post-transplant care. Several incidents demonstrated the challenges with coordinated care among multiple health care providers. Contributing factors shared included medication review discrepancies and ambiguous documentation.

Although not identified in the analysis, another potential factor, especially for the many patients who live outside of centres that provide specialized post-transplant care, is the need to easily access these services. Virtual care offers an important opportunity in such access and in the seamless transfer of information to community care providers. This holds especially true in the context of the current COVID-19 pandemic, during which post-discharge virtual care has been recommended, where feasible, to prevent hospital-based infection.6

![]()

TIP: Create a post-transplant care plan with the patient/family that includes regular meetings, an up-to-date medication list, and key considerations for medication use and monitoring.

Incident Example

A patient with a history of organ transplant requested their anti-rejection medications while in the emergency department for an unrelated matter. Staff informed the patient that the medication would not be given until the patient had been transferred to a unit, which resulted in a significant delay in administration.

CONCLUSION

Errors in the management of anti-rejection drugs in patients who have undergone organ transplant can lead to loss of the grafted organ or increased susceptibility to infections. This thematic analysis highlights areas of risk in the medication-use system and shares selected safety tips, including preventing product selection errors, building alerts and checks into the order entry systems, and continuously improving coordination of care.

![]()

The Canadian Medication Incident Reporting and Prevention System (CMIRPS) is a collaborative pan-Canadian program of Health Canada, the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI), the Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada (ISMP Canada) and Healthcare Excellence Canada (HEC). The goal of CMIRPS is to reduce and prevent harmful medication incidents in Canada.

Funding support provided by Health Canada. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of Health Canada.

The Healthcare Insurance Reciprocal of Canada (HIROC) provides support for the bulletin and is a member owned expert provider of professional and general liability coverage and risk management support.

The Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada (ISMP Canada) is an independent national not-for-profit organization committed to the advancement of medication safety in all healthcare settings. ISMP Canada’s mandate includes analyzing medication incidents, making recommendations for the prevention of harmful medication incidents, and facilitating quality improvement initiatives.

Report Medication Incidents (Including near misses)

Online: ismpcanada.ca/report/

Phone: 1-866-544-7672

ISMP Canada strives to ensure confidentiality and security of information received, and respects the wishes of the reporter as to the level of detail to be included in publications.

Stay Informed

Subscribe to the ISMP Canada Safety Bulletins and Newsletters.

This bulletin shares information about safe medication practices, is noncommercial, and is therefore exempt from Canadian anti-spam legislation.

Contact Us

Email: cmirps@ismpcanada.ca

Phone: 1-866-544-7672

©2025 Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada.