Deprescribing: Managing Medications to Reduce Polypharmacy

This bulletin shares a story of deprescribing, from the clinical considerations identified by the practitioner to the life-changing outcome, as described by the individual involved.

𝗦𝗶𝗱𝗲𝗯𝗮𝗿𝘀:

- Opioids for Pain After Surgery—Patient Handout

- Don't Be Embarrassed to Talk to Your Pharmacist

INTRODUCTION

- Deprescribing must be done in partnership with the patient.

- The use of validated processes, algorithms, and tools may help with the incorporation of deprescribing into clinical practice.

- Deprescribing requires close, consistent monitoring of the patient to ensure that the medication taper or discontinuation is both safe and effective.

The World Health Organization has highlighted polypharmacy as one of the key focus areas of its Third Global Patient Safety Challenge, Medication Without Harm.1 The term “polypharmacy” has multiple definitions, but the most common is the concurrent use of 5 or more medications (including both prescription and nonprescription products) by a single individual.1-4 Polypharmacy exists when the theoretical benefits of multiple medications is outweighed by the negative effects of the sheer number of medications.3,5 Polypharmacy is not solely about the number of medications used, but also about the effectiveness, utility, and potential harm of each medication, both individually or in combination.

Deprescribing is a method to address polypharmacy.6 It is defined as a planned process of reducing or stopping medications that may no longer be of benefit or that may be causing harm, with the ultimate goal of reducing medication burden and improving quality of life.7 This bulletin shares a story of deprescribing, from the clinical considerations identified by the practitioner to the life-changing outcome, as described by the individual involved.

INCIDENT EXAMPLE

Deprescribing must be done in partnership with the patient.

A patient with several medical problems had received prescriptions for more than 15 medications from the family doctor and multiple specialists. The patient reported experiencing considerable symptoms, including episodes of gastroparesis requiring frequent emergency department visits. The patient’s complex medical history, multiple presentations seeking care, and polypharmacy prompted review by a pharmacist. The pharmacist worked with the patient and key healthcare practitioners to develop a plan to reduce the medications. Over the next several months, several anticholinergic and psychotropic medications were tapered and then discontinued. One example of a drug that was discontinued after tapering was high-dose amitriptyline, which was no longer warranted and which was contributing to the gastroparesis. The deprescribing process was just one of several interventions, including nonpharmacological treatments and close collaboration with other healthcare practitioners to address and control the various conditions. The patient reported that these interventions were life-saving.

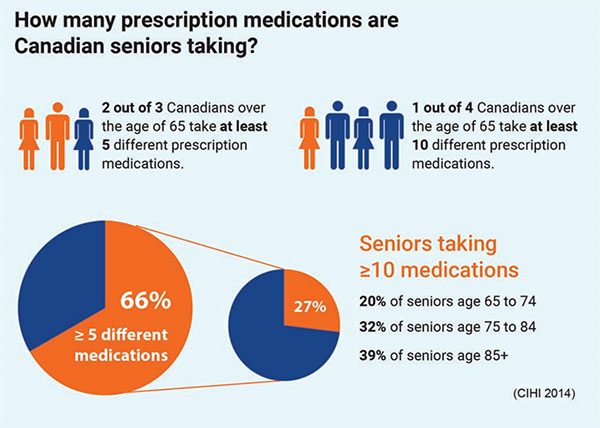

INCIDENCE AND ECONOMIC BURDEN OF POLYPHARMACY

Polypharmacy is more common among seniors, as well as individuals with mental health disorders, both groups who are especially at risk of adverse outcomes.8 Data collected by the Canadian Institute for Health Information about the incidence of polypharmacy in Canadian seniors is illustrated in Figure 1. About 25% of seniors over the age of 65 take at least 10 medications, and this percentage increases to almost 40% in seniors over the age of 85. There is an 8-fold greater risk of drug–drug interactions as the number of medications prescribed increases from 2 to 10. Additive adverse drug effects and drug–disease interactions contribute to potential negative outcomes.9 The cost of potentially inappropriate medication use in Canada has been estimated at $419 million annually, and the cost of treating the harmful effects of these medications is estimated to be $1.4 billion every year.10

Figure 1. Canadian seniors’ prescription medicationtaking data9

INCORPORATING DEPRESCRIBING INTO PRACTICE

Healthcare practitioners may be prompted to consider the possibility of deprescribing in situations such as: a change in a patient’s clinical condition; progression of an existing condition (e.g., dementia); an increased need for assistance with daily activities; an increased risk of falls; a decline in weight or liver/renal function; or following a transition in care. Certain electronic health record programs and pharmacy systems have the capacity to search systematically for patients who may benefit from deprescribing, according to criteria such as the number of current medications or the presence of specific high-risk drugs. This feature could be used by practitioners to identify patients in need of a medication review and to consider whether deprescribing is appropriate.

INITIAL APPROACH AND CARE TEAM–PATIENT PARTNERSHIP

Deprescribing must be done in partnership with the patient and the healthcare practitioners caring for that patient. The process begins with the practitioner(s) and the patient (and/or caregiver) carefully evaluating all of the patient’s medications. Discussions about medication choices should involve patient-driven care goals and must balance the expected benefit of drug therapy against any possible harm.

Resources such as the 5 Questions to Ask about Your Medications and the EMPOWER brochures can be used to initiate discussions about the need to review and potentially reduce or discontinue medications. These and other shared decision-making tools have been shown to improve people’s knowledge and realistic perception of outcomes and associated risks.11,12

Patients may be more open to change when they have a greater understanding of the benefits of deprescribing (e.g., elimination of bothersome side effects). It is also important to partner with the patient’s care team (e.g., family/caregivers, primary care practitioner, community pharmacist, medical specialists), to engage them in monitoring and to prevent medications that are being tapered or discontinued from inadvertently being restarted.

For most medications, it is best to plan one change at a time, rather than discontinuing/tapering several medications simultaneously. After evaluating the effects of 1 change, further adjustments to the medication regimen can be made as appropriate.

DEPRESCRIBING RESOURCES

The use of validated processes, algorithms, and tools may help with the incorporation of deprescribing into clinical practice.13 Choosing Wisely Canada has recently released toolkits14 on how to reduce and discontinue benzodiazepines, proton pump inhibitors, and antipsychotics; these toolkits include detailed algorithms and patient resources to optimize utilization (Box 1). The Canadian Deprescribing Network provides links to additional useful resources for patients (Box 1).15

Box 1. Useful Resources for Deprescribing

- Deprescribing algorithms

- Canadian Deprescribing Network (resources for patients)

- Choosing Wisely Canada (deprescribing toolkits)

- How to taper medications

- Opioid Tapering Templates:

- Guideline for Deprescribing Cholinesterase Inhibitors and Memantine

Other resources available to help in identifying medications to be discontinued or reduced include the STOPP tool,16 the Hierarchy of Utility of Medications,17 the Beers Criteria18 and the NO TEARS tool (Box 2).19

Box 2. NO TEARS Tool19

In the incident example, a review based on principles in the NO TEARS tool identified several medications that could be reduced or discontinued. For example, the amitriptyline was no longer warranted given the patient’s goals of care, and this drug’s significant anticholinergic effects were contributing to the patient’s gastroparesis and other symptoms. With agreement from the prescriber and the patient, the pharmacist developed a plan to taper the amitriptyline dose over a period of a month. After the amitriptyline had been discontinued, a plan to deprescribe other medications was undertaken.

MONITORING

Deprescribing requires close, consistent monitoring of the patient to ensure that the medication taper or discontinuation is both safe and effective. Patients, family/caregivers, and other community care providers need to know what symptoms and side effects to look out for and when to seek medical attention (Box 3). In the incident example, the patient was educated about how to identify symptoms associated with amitriptyline withdrawal and knew to report these effects and/or feelings of depression to the prescriber. Both the pharmacist and the prescriber stayed in touch with the patient during the tapering period.

Box 3. Monitoring Considerations when Deprescribing

Monitor for changes in the patient’s health status, such as the following:

- Drug withdrawal reactions.20

- Changes in the pharmacodynamics of other medications being taken concurrently (e.g., altered receptor sensitivity, cytochrome P450 liver enzyme dysregulation, drug interaction-related dosage adjustments).

- Return of symptoms from the original medical condition for which the medication was prescribed.

CONCLUSION

Deprescribing provides an opportunity to improve patient health outcomes by reducing the use of potentially harmful and/or ineffective medications. Attention is needed to ensure that every prescribed medication is assessed carefully, both on initial prescription and at regular intervals thereafter. With the initiation of every medication, prescribers may want to discuss a time to re-evaluate the medication with the patient. Practitioners are urged to actively consider deprescribing as part of ongoing treatment evaluation and medication management, with the goal of minimizing preventable harm and reducing medication burden. By partnering with patients to discuss these strategies, practitioners can better engage patients and their caregivers, so they understand whether and when tapering or discontinuation of medications is appropriate.

![]()

The Canadian Medication Incident Reporting and Prevention System (CMIRPS) is a collaborative pan-Canadian program of Health Canada, the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI), the Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada (ISMP Canada) and Healthcare Excellence Canada (HEC). The goal of CMIRPS is to reduce and prevent harmful medication incidents in Canada.

Funding support provided by Health Canada. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of Health Canada.

The Healthcare Insurance Reciprocal of Canada (HIROC) provides support for the bulletin and is a member owned expert provider of professional and general liability coverage and risk management support.

The Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada (ISMP Canada) is an independent national not-for-profit organization committed to the advancement of medication safety in all healthcare settings. ISMP Canada’s mandate includes analyzing medication incidents, making recommendations for the prevention of harmful medication incidents, and facilitating quality improvement initiatives.

Report Medication Incidents (Including near misses)

Online: ismpcanada.ca/report/

Phone: 1-866-544-7672

ISMP Canada strives to ensure confidentiality and security of information received, and respects the wishes of the reporter as to the level of detail to be included in publications.

Stay Informed

Subscribe to the ISMP Canada Safety Bulletins and Newsletters.

This bulletin shares information about safe medication practices, is noncommercial, and is therefore exempt from Canadian anti-spam legislation.

Contact Us

Email: cmirps@ismpcanada.ca

Phone: 1-866-544-7672

©2025 Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada.