- Communicate with patients and their caregivers when reviewing prescription information during the transition at discharge.

- Implement standardized discharge processes to enable the creation of discharge prescriptions that are accurate, unambiguous, appropriate, and understood by all in the patient’s circle of care.

- Community caregivers and providers are encouraged to review how they process hospital discharge prescriptions to minimize or improve upon error-prone processes and procedures.

INTRODUCTION

During a hospital stay, a patient’s medication regimen may undergo multiple changes. If these changes are not captured accurately on the patient’s discharge prescription, these discrepancies can lead to medication errors. A recent study of the medication lists for geriatric patients at the time of discharge from hospital revealed that 56% of patients experienced at least 1 prescribing error.1 Such errors can result in patient harm, readmission to hospital, and/or an increased workload for care providers, as well as having the potential to undermine patients’ confidence in the healthcare system. A multi incident analysis of medication incidents involving discharge prescriptions was conducted to better understand the challenges around the creation and processing of hospital discharge prescriptions and to share opportunities for system-based improvements.

METHODOLOGY AND QUANTITATIVE FINDINGS

Reports of medication incidents related to discharge prescriptions were extracted from voluntary reports* submitted to 3 ISMP Canada reporting databases (Individual Practitioner Reporting, Community Pharmacy Incident Reporting, and Consumer Reporting) and the National System for Incident Reporting† (NSIR) from April 1, 2010, to November 8, 2016. Key phrases used to search the databases included “discharge prescription”, “discharge Rx”, “hospital prescription”, “hospital Rx”. A total of 156 incidents were extracted for review. Reports unrelated to discharge prescriptions, those containing insufficient detail, and duplicate entries were omitted from the dataset. After these exclusions, 134 incidents were included in the final analysis, which was conducted according to the methodology outlined in the Canadian Incident Analysis Framework.2 About 10% of these cases resulted in harm.

QUALITATIVE ANALYSIS

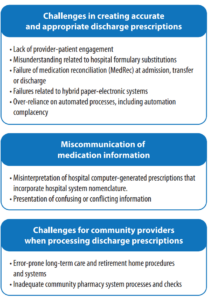

Analysis of the incidents identified 3 main themes and associated subthemes (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. Main themes and subthemes from the qualitative analysis

Theme: Challenges in Creating Accurate and Appropriate Discharge Prescriptions

A key component of the patient discharge process is the creation of accurate and appropriate discharge prescriptions. Table 1 highlights the challenges identified within this theme that led to problems with discharge prescriptions.

Factors contributing to the incidents included lack of a systematic discharge medication reconciliation (MedRec) process that incorporates patient engagement, lack of a standardized discharge prescription template across hospitals, and missed opportunities for communication with community pharmacists. The Facilitating Medication Safety at Transitions toolkit and checklist are available for hospitals to help re-examine some of these processes, with the goal of optimizing the transition of patients and their medications at discharge.

- Recommendation: Implement standardized discharge processes to enable the creation of discharge prescriptions that are accurate, unambiguous, appropriate, and understood by all in the patient’s circle of care.

There is preliminary evidence that electronic MedRec solutions, especially those that incorporate the creation of a discharge prescription, can reduce prescribing discrepancies and errors at discharge.3 However, with the adoption of new technologies, new sources of error can arise; therefore, hospitals that are designing electronic systems are encouraged to refer to the Discharge Medication Reconciliation – Clinical Requirements expert panel workshop proceedings for guidance.4

Theme: Miscommunication of Medication Information

Discharge prescriptions are the most common method of communicating changes to medication regimens to the next care providers, which makes the information contained in these documents vital. The multi incident analysis showed that computer-generated discharge prescriptions included hospital system nomenclature that was misinterpreted by community providers, and led to errors and delays in the dispensing process. Use of ambiguous dose and nonstandard abbreviations were noted. Opportunities exist both to standardize discharge prescriptions and to have community stakeholders involved in testing the clarity of hospitals’ computer-generated discharge prescriptions.

Incident Example

A patient recently discharged from hospital was given a computer-generated discharge prescription that read “warfarin 4mg WRF”. The community pharmacist interpreted “WRF” as “Wed, Thurs, Fri”. Upon checking with the hospital, however, the pharmacist discovered that “WRF” was a short form for “WaRFarin” used by that particular hospital to indicate its usual warfarin daily dose administration time.

TABLE 1. Subthemes for challenges related to creating accurate and appropriate discharge prescriptions

Effectively communicating key medication information, including changes in therapy, to the patient and family is integral to the success of the discharge medication plan. This analysis identified many gaps and discrepancies in the information provided to patients, including provision of information that conflicted with the directions on the prescription, which resulted in the patient using medication(s) in a different way than intended. ISMP Canada has previously recommended that prescriptions be written in a manner that patients can read and understand (e.g., without unnecessary abbreviations).5

Hospital staff can engage patients and caregivers by using the “5 Questions to Ask about your Medications” to foster discussions about medication changes during this critical time and by using teach-back techniques to enhance uptake. There is also evidence that a post-discharge follow-up phone call to certain high-risk patients can help to prevent readmissions.6

- Recommendation: Engage patients and their caregivers at or before discharge to communicate changes in the medication regimen and to support an independent check of the discharge prescriptions.

Theme: Challenges for Community Providers when Processing Discharge Prescriptions

The analysis identified unique challenges faced by community providers in dealing with hospitals’ discharge prescriptions. For example, some community pharmacies that service retirement or long-term care facilities use a system that requires the facilities to transcribe information from the hospital discharge prescription onto a digital MedRec form. This form is then sent to the community pharmacy for dispensing. The additional process of interpretation and transcription led to errors, including omission of medications, ordering of incorrect drugs, and dosing errors. When a resident is discharged to a long-term care facility, the hospital’s original discharge prescriptions and/or discharge plan should be shared with the dispensing pharmacy to support accurate dispensing and thorough MedRec processes.

Incident Example

A long-term care resident who had been in hospital was given a prescription for a beta-blocker at the time of discharge back to the care facility. The nurse transcribed the discharge prescription onto the partner pharmacy’s order form, but misinterpreted the instructions. Fortunately, the mistake resulted in a subtherapeutic dose of the medication, which was questioned by the pharmacist. After the pharmacist requested a copy of the hospital’s discharge prescription form, the discrepancy was resolved.

- Recommendation: Long-term care and retirement facilities should forward to their partner community pharmacies, the hospital’s discharge prescriptions along with the electronic order forms containing the transcribed information, to support an independent check process.

Patients are often discharged home with prescriptions for a large number of medications, including both new therapies started in hospital as well as preadmission medication to be continued. These latter prescriptions are handled in various ways by the community pharmacy. New prescriptions for existing and unchanged therapies are often logged as inactive or “for future use” in the computer, meaning that they will be activated and dispensed when the current prescription runs out. Prescriptions with changes are processed by copying and modifying existing orders in the computer, while also discontinuing the original order. This helps with pharmacy workflow and saves time in processing the prescriptions. However, the copying process is error-prone.

- Recommendation: Community pharmacies processing hospital discharge prescriptions should minimize “electronic copying” when entering changes into pharmacy dispensing systems.

CONCLUSION

The creation of a complete, accurate, and unambiguous hospital discharge prescription is a vulnerable point in the process of transferring medication information. Findings from this multi-incident analysis concurred with the findings of an observational study that reported omissions and incomplete, conflicting, or unclear information in many discharge prescriptions.7 The analysis findings also led to recommendations. Opportunities exist for hospitals to implement a standardized discharge process that includes clarifying discrepancies, validating the accuracy, completeness, and clinical appropriateness of the prescriptions, and a review of the discharge regimen with patients and caregivers.1,8 Additionally, it is important to capture incidents related to discharge prescriptions in hospital incident reporting systems so vulnerable processes and systems can be identified. Community partners can likewise review how they handle hospital discharge prescriptions in the context of the error-prone processes identified in this analysis to minimize errors.

![]()

The Canadian Medication Incident Reporting and Prevention System (CMIRPS) is a collaborative pan-Canadian program of Health Canada, the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI), the Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada (ISMP Canada) and Healthcare Excellence Canada (HEC). The goal of CMIRPS is to reduce and prevent harmful medication incidents in Canada.

Funding support provided by Health Canada. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of Health Canada.

The Healthcare Insurance Reciprocal of Canada (HIROC) provides support for the bulletin and is a member owned expert provider of professional and general liability coverage and risk management support.

The Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada (ISMP Canada) is an independent national not-for-profit organization committed to the advancement of medication safety in all healthcare settings. ISMP Canada’s mandate includes analyzing medication incidents, making recommendations for the prevention of harmful medication incidents, and facilitating quality improvement initiatives.

Report Medication Incidents (Including near misses)

Online: ismpcanada.ca/report/

Phone: 1-866-544-7672

ISMP Canada strives to ensure confidentiality and security of information received, and respects the wishes of the reporter as to the level of detail to be included in publications.

Stay Informed

Subscribe to the ISMP Canada Safety Bulletins and Newsletters.

This bulletin shares information about safe medication practices, is noncommercial, and is therefore exempt from Canadian anti-spam legislation.

Contact Us

Email: cmirps@ismpcanada.ca

Phone: 1-866-544-7672

©2025 Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada.