Optimizing Medication Safety in Virtual Primary Care

During the COVID-19 pandemic, virtual care has allowed many Canadians to access health care remotely. The growth of virtual care has also highlighted the need to optimize the safety of this approach to care. This bulletin shares findings from an analysis of a cluster of medication incidents that occurred during the provision of virtual primary care. Recommendations are made to inform continuous improvement.

Virtual care has been defined as “any interaction between patients and/or members of their circle of care, occurring remotely, using any forms of communication or information technologies, with the aim of facilitating or maximizing the quality and effectiveness of patient care.”1

INTRODUCTION

During the COVID-19 pandemic, virtual care has allowed many Canadians to access health care remotely. The growth of virtual care has also highlighted the need to optimize the safety of this approach to care. This bulletin shares findings from an analysis of a cluster of medication incidents that occurred during the provision of virtual primary care. Recommendations are made to inform continuous improvement.

METHODOLOGY

Medication incident reports related to virtual primary care were identified from 3 ISMP Canada databases (Individual Practitioner Reporting, Consumer Reporting, and the National Incident Data Repository for Community Pharmacies) from January 2020 to March 2022. Search terms included virtual, video, tele*, online, delivery, and remote. A total of 4682 incidents were extracted. Incidents were excluded if they occurred outside of primary care, or the incident report did not provide sufficient detail related to the virtual care experience. After exclusions, 58 reports were included for analysis.

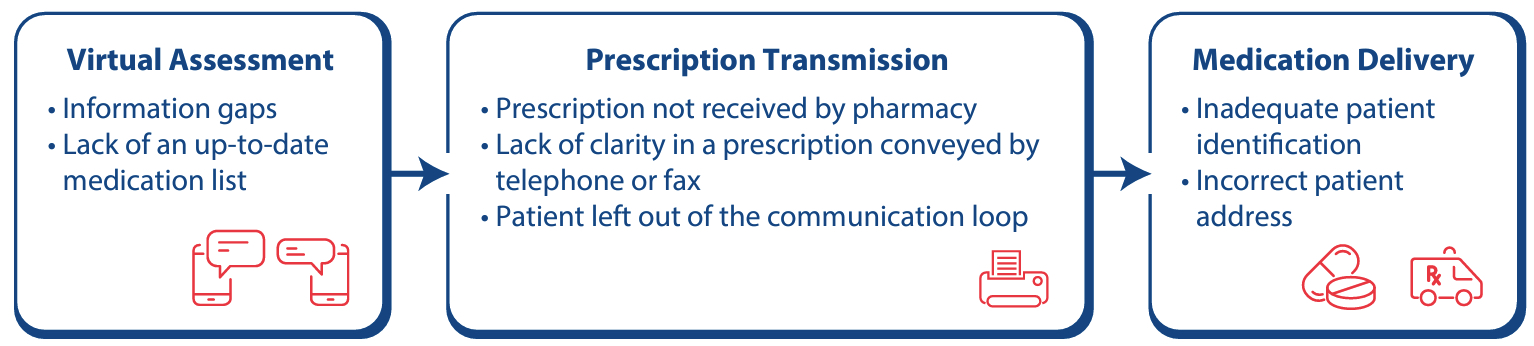

Preliminary findings from the analysis of reported incidents were shared with an Advisory Panel¥ for comment, feedback and input to the development of recommendations. Areas of vulnerability identified in the analysis are described in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1. Areas of vulnerability identified in an analysis of virtual primary care–related medication incidents.

AREAS OF VULNERABILITY

Virtual Assessment

![]()

During a virtual care appointment, particularly one taking place over the telephone, the health care provider is restricted in the ability to physically examine the patient and to see their medications.

- Information Gaps

Incident example: During a telephone appointment, the physician was unable to diagnose the patient’s shingles because of a lack of visual technology. As a result of a delay, the patient missed the opportunity to be treated within the ideal timeframe for a better therapeutic outcome. - Lack of an Up-to-Date Medication List

Incident example: A patient had a telephone appointment with their physician to renew prescriptions; the prescriptions were then faxed to the pharmacy, filled, and provided to the patient. The dispensed medications included a diuretic; however, the patient alerted the pharmacist that their diuretic had been stopped years ago. The pharmacy contacted the physician, who clarified that an outdated medication list had been inadvertently used to authorize the renewals.

These findings are supported by reports in the literature. Virtual communication can limit the information available to the care provider, potentially impeding timely diagnoses and medication reconciliation.2 Despite potential limitations, a survey indicated that most patients would be willing to use virtual care for follow-up, prescription renewal, urgent minor issues, and new health concerns.3 There is an opportunity to enhance the safety of virtual care so that it can be used optimally, when preferred and appropriate.

Recommendations

- Facilitate a visual form of communication in the virtual care platform (e.g., video conferencing, photo-sharing) to optimize the quality of patient care, including timely diagnosis and therapeutic management.

- Confirm current medication use with the patient before prescribing or renewing medications.

- The patient can contact their community pharmacist for a virtual medication review, before the appointment, to obtain an up-to-date medication list.4

- Consider implementing a “virtual waiting room” where a nurse or pharmacist completes a best possible medication history with the patient and updates the medication list just before the appointment.5

- Consider integrating a medication reconciliation form and/or checklist for use prior to appointments.

Prescription Transmission

![]()

There are various ways that prescriptions are transmitted following a virtual appointment (e.g., e-prescribing service, telephone, and fax). The benefits of e-prescribing have been outlined in a joint statement from the Canadian Association of Chain Drug Stores and the Canadian Pharmacists Association.6 Findings from this analysis demonstrate the opportunity to increase patient engagement during prescription transmission.

- Prescription Not Received by Pharmacy

Incident example: The patient had a virtual care appointment by telephone with their doctor. A prescription for an antibiotic was to be faxed to the pharmacy. When the patient arrived at the pharmacy, the fax had not been received. This delayed the initiation of antibiotic therapy. - Lack of Clarity in a Prescription Conveyed by Telephone or Fax

Incident example: The prescriber ordered a medication refill by telephone. The person taking the call at the pharmacy misheard the name of the medication, which resulted in the wrong drug being dispensed. At home, the patient did not recognize the medication and checked with the prescriber; the prescriber confirmed that an error had occurred. - Patient Left Out of the Communication Loop

Incident example: After a virtual appointment, a prescription for a tapering regimen of corticosteroid was sent to the pharmacy. The patient did not realize that the tapering prescription was meant to continue beyond the first fill. When the patient finished the medication in the vial and did not order a refill, the abrupt cessation of the medication caused a flare-up of their condition and readmission to hospital.

During or following a virtual care visit, the prescriber transmits any needed prescriptions to the patient’s pharmacy, either by e-prescribing service, telephone, or fax. In a recent survey, 28% of patients who had a prescription sent directly to a pharmacy experienced issues (e.g., prescription did not arrive at the pharmacy or was sent to the wrong pharmacy).7 Miscommunication related to telephone and fax transmission of prescriptions to pharmacies is well documented8 and was evident in the incidents in the current analysis.

The process of remote transmission of prescriptions does not typically include providing an electronic copy to patients; as a result, patients are not positioned to confirm their understanding of the medication prescribed and dosing instructions, nor the pharmacy to which the prescription was transmitted. In a recent co-design event on virtual primary care, with patients and health care providers, patients reported feeling out of the communication loop with virtual care appointments.9

Recommendations

- Provide the patient with an electronic summary of the medication changes (e.g., discontinuations, newly added medications) and medication renewals after the virtual care appointment. This supports patients in taking an active role in the safety of their care.

- Confirm the patient’s pharmacy using 2 identifiers (e.g., name, address) before transmitting the prescription via e-prescribing service, telephone, or fax.

- Continue to use strategies to support safer transmission and receipt of telephone orders, such as allowing sufficient time to state the order clearly and for the person receiving it to read it back.8

- Consider a communication mechanism for patients to be kept informed of the progress of the prescription filling process. For example, some pharmacies have an auto-text service to inform patients when their prescription is ready for pick-up.

Medication Delivery

![]()

Home delivery of medications is convenient for patients, but this service carries some risk.

- Inadequate Patient Identification

Incident example: The automatic refill list for the day included 2 patients using the same medication at the same dose and frequency. The patients were contacted to arrange delivery. The first patient responded, but the second patient’s prescription was inadvertently delivered to them. The error was realized when the second patient called to arrange delivery. - Incorrect Patient Address

Incident example: The patient’s agent brought a new prescription to the pharmacy and requested a delivery. The patient’s address was not confirmed, and the medication was delivered to an old address.

Medication incidents involving delivery errors can occur when patients have the same or similar names and/or addresses. Medications delivered to the wrong patient constitute a breach of privacy for the intended patient, and such errors may result in harm for both the intended patient and the unintended recipient (if ingestion occurs).

ISMP Canada continues to receive reports related to medication delivery; a recent report described a gap in counselling for delivered medications.

Recommendations

- Confirm 2 patient identifiers (e.g., name and address) before delivery of medications, at the pharmacy and again at the patient’s home.

- Instruct the delivery team not to leave medications at the door and to return medications to the pharmacy if unable to make the delivery to the correct person.

- Implement processes to identify new prescriptions scheduled for delivery and requiring counselling.

CONCLUSION

This analysis identified vulnerabilities and improvement strategies for medication safety in virtual care assessments, prescription transmission, and medication delivery. Although some of the findings may not be unique to virtual care, they reflect the experiences with new technologies and approaches, and demonstrate how shared learning can be used to inform continuous improvement.

![]()

The Canadian Medication Incident Reporting and Prevention System (CMIRPS) is a collaborative pan-Canadian program of Health Canada, the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI), the Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada (ISMP Canada) and Healthcare Excellence Canada (HEC). The goal of CMIRPS is to reduce and prevent harmful medication incidents in Canada.

Funding support provided by Health Canada. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of Health Canada.

The Healthcare Insurance Reciprocal of Canada (HIROC) provides support for the bulletin and is a member owned expert provider of professional and general liability coverage and risk management support.

The Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada (ISMP Canada) is an independent national not-for-profit organization committed to the advancement of medication safety in all healthcare settings. ISMP Canada’s mandate includes analyzing medication incidents, making recommendations for the prevention of harmful medication incidents, and facilitating quality improvement initiatives.

Report Medication Incidents (Including near misses)

Online: ismpcanada.ca/report/

Phone: 1-866-544-7672

ISMP Canada strives to ensure confidentiality and security of information received, and respects the wishes of the reporter as to the level of detail to be included in publications.

Stay Informed

Subscribe to the ISMP Canada Safety Bulletins and Newsletters.

This bulletin shares information about safe medication practices, is noncommercial, and is therefore exempt from Canadian anti-spam legislation.

Contact Us

Email: cmirps@ismpcanada.ca

Phone: 1-866-544-7672

©2025 Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada.