INTRODUCTION

The Canadian Medication Incident Reporting and Prevention System (CMIRPS) continues to receive reports from practitioners that describe concerns with labelling and packaging. A multi-incident analysis was conducted to better understand current labelling and packaging vulnerabilities specific to high-alert medications1 provided in vials and ampoules. Error prevention strategies are proposed to complement the recommendations in the Good Label and Package Practices Guide for Prescription Drugs.2

METHODOLOGY

Medication incidents associated with high-alert medications in vials and ampoules were extracted from reports submitted to ISMP Canada’s Individual Practitioner Reporting (IPR) and National Incident Data Repository for Community Pharmacies (NIDR) databases and the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) National System for Incident Reporting (NSIR) database* over the 3-year period from April 1, 2019, to March 31, 2022.

To manage the scope of the analysis, the medications for the database searches were selected from a list of high-alert medications provided in vials or ampoules and typically stocked in emergency departments. However, for purposes of the analysis, there was no limit on the care settings in which the incidents occurred. Additional search terms included “vial”, “ampoule”, “package”, “label”, “high-alert”, “similar”, and “identical”. Errors involving non-commercial labelling (e.g., pharmacy-printed labels) and other types of packaging (e.g., prefilled syringes, infusion bags) were excluded. Errors associated with insulin and opioid products were also excluded, as labelling- and packaging-related issues pertaining to these types of medications have been frequently reported and previously analyzed, with specific recommendations made.3-8

QUANTITATIVE FINDINGS

A total of 2394 incident reports were screened for inclusion, of which 114 met the inclusion criteria: 26 incident reports from the ISMP Canada databases and 88 incident reports from the CIHI database.†

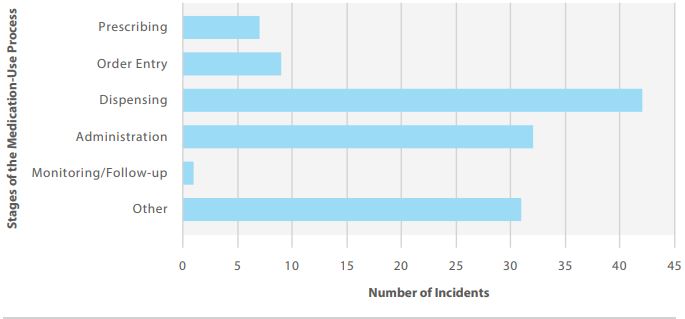

Figure 1 shows the top 5 medications most frequently cited in the analyzed dataset, and Figure 2 shows the stages of the medication-use process involved.

FIGURE 1. Top 5 medications involved in reported incidents (excludes insulins and opioids).

FIGURE 2. Stages of the medication-use process involved in reported incidents.

QUALITATIVE ANALYSIS

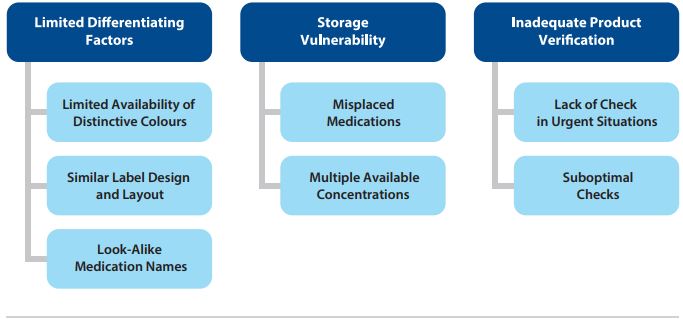

FIGURE 3. Themes and subthemes identified in the analysis.

Three main themes and associated subthemes were identified through the analysis (Figure 3).

Theme: Limited Differentiating Factors

For medications provided in vials and ampoules, labelling, packaging and storage are important factors in the prevention of medication errors for the following general reasons:

- Vial and ampoule shapes and sizes are limited and not distinctive.

- Injectable solutions are often clear liquids, which are indistinguishable from one another.

- Space available on the label for printed information is limited, which may necessitate use of smaller font sizes, affecting readability.

The most frequently reported factors contributing to mix-ups were similar colours, similar label designs and layouts, and similar medication names.

- Limited Availability of Distinctive Colours: In this analysis, medication vial caps with the same colour were frequently reported as a cause for concern or were implicated in errors. Although colour differentiation can support identification of the intended product, the number of colours that can be accurately differentiated, or readily identified without errors, is limited to 12.9,10 Recognizing that a hospital may typically carry 200 or more different injectable products in their inventory, use of distinct colours for product differentiation is not possible. Additionally, colour changes to a product in inventory (including intentional changes by the manufacturer and changes due to shortages) may inadvertently increase the risk of a look-alike error.

- Similar Label Design and Layout: Differences on product labels used to differentiate among various strengths of a medication from the same manufacturer may not be easily perceived. For products from different manufacturers, vial and ampoule labels may share a similar visual style (e.g., type style, content layout).

Incident Example: A mix-up between a vial of rocuronium and succinylcholine was reported. These vials have a standardized red cap and warning designed to prevent fatal errors that have occurred with neuromuscular blocking agents. Preventing mix ups within this group of medications requires storage and practice safeguards.

Theme: Storage Vulnerability

Storage was one of the most frequently reported factors contributing to medications errors in the analyzed dataset, which is reflected in the following subthemes.

- Misplaced Medications: In some reports, look-alike medications (i.e., those with similar-sized vials/ampoules and labels) that were received at the same time were mistakenly stored together in the pharmacy. In other reports, medications were placed in the wrong area when returning medications to stock.

- Multiple Available Concentrations: Medications in vials and ampoules are commonly available in more than one concentration. Different concentrations of the same medication were stored together instead of being separated.

Incident Example: A patient asked for pain medication during a shift change. A vial of midazolam was retrieved from a drawer instead of the intended hydromorphone. By the time the error was recognized, the cap had been removed in readiness for administration but was not given to the patient.

Theme: Inadequate Product Verification

Safeguards against selection errors (e.g., verification by pharmacy, dispensing by means of an automated dispensing unit [ADU], use of barcoding) may not be in place in all care areas. The analysis showed that independent double checks for product verification were sometimes overlooked or insufficient during medication dispensing and administration. Reporters also described situations in which staffing shortages meant that replacement nurses were less familiar with local processes for accessing medications and the need for double checks.

- Lack of Check in Urgent Situations: Health care requires efficiency without compromising accuracy and safety. Stress and poor individual performance were often reported as contributing factors in urgent situations that did not allow for an extra check.

- Suboptimal Checks: Human factors (e.g., confirmation bias) play a role in suboptimal checks. An independent double check process, including use of technology (e.g., barcoding), is important to support product selection, dose preparation, and medication administration.

Incident Example: A vial of epinephrine was inadvertently retrieved from the supply cart instead of the intended vial of ondansetron. The selection error was not recognized, despite a double-check process involving another staff member. The patient experienced an adverse reaction to the epinephrine, which led to identification of the error.

KEY RECOMMENDATIONS

- Integrate a high-leverage product verification strategy (e.g., barcoding) for high-alert medications identified by the organization in each step of the medication-use process, including stocking and restocking.

- Provide medications in a ready-to-use format (e.g., premixed minibag) to reduce selection, preparation, and administration errors with medications in look-alike vials and ampoules.11

- Store vials on their sides, with labels facing up; use storage compartments to separate look-alike products.11 Technology, such as automated dispensing units, can support safe storage

- Add auxiliary warnings to storage containers, where appropriate (e.g., for neuromuscular blocking agents stored outside the operating room).12

- Communicate product changes to alert point-of-care providers.

- Consider error potential when making purchasing decisions.

CONCLUSION

The Good Label and Package Practices Guide for Prescription Drugs2 was developed to guide manufacturers in designing safer labels and packages. Many manufacturers have implemented safe practices outlined in the Guide and there have been improvements made to labels and packages. Continuous reporting and learning will inform updates to the Guide and also help identify strategies for quality improvement in medication management and the prevention of errors and associated harm. This multi-incident analysis demonstrates and serves as a reminder that substitution errors with vials or ampoules containing high-alert medications continue to be reported. Given that there are limits to the variety of shapes, sizes, colours, designs, and layouts for labelling and packaging, it is important to incorporate system safeguards to reduce reliance on product appearance only.

![]()

The Canadian Medication Incident Reporting and Prevention System (CMIRPS) is a collaborative pan-Canadian program of Health Canada, the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI), the Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada (ISMP Canada) and Healthcare Excellence Canada (HEC). The goal of CMIRPS is to reduce and prevent harmful medication incidents in Canada.

Funding support provided by Health Canada. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of Health Canada.

The Healthcare Insurance Reciprocal of Canada (HIROC) provides support for the bulletin and is a member owned expert provider of professional and general liability coverage and risk management support.

The Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada (ISMP Canada) is an independent national not-for-profit organization committed to the advancement of medication safety in all healthcare settings. ISMP Canada’s mandate includes analyzing medication incidents, making recommendations for the prevention of harmful medication incidents, and facilitating quality improvement initiatives.

Report Medication Incidents (Including near misses)

Online: ismpcanada.ca/report/

Phone: 1-866-544-7672

ISMP Canada strives to ensure confidentiality and security of information received, and respects the wishes of the reporter as to the level of detail to be included in publications.

Stay Informed

Subscribe to the ISMP Canada Safety Bulletins and Newsletters.

This bulletin shares information about safe medication practices, is noncommercial, and is therefore exempt from Canadian anti-spam legislation.

Contact Us

Email: cmirps@ismpcanada.ca

Phone: 1-866-544-7672

©2025 Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada.