Pharmacists’ Scope of Practice in Community Pharmacy: Medication Incident Reporting Informs Continuous Improvement

In Canada, the current scope of practice for pharmacists permits provision of care beyond historical roles of medication compounding, medication dispensing, and counselling. This bulletin highlights opportunities for continuous quality improvement.

INTRODUCTION

In Canada, the current scope of practice for pharmacists permits provision of care beyond historical roles of medication compounding, medication dispensing, and counselling. Depending on the jurisdiction, pharmacists may independently prescribe medications, renew/extend and adapt/adjust prescriptions, order and interpret laboratory tests, provide point-of-care-testing, and prescribe and administer injections and vaccinations.1 This bulletin highlights opportunities for continuous quality improvement by sharing learning from a multi-incident analysis (MIA) of reports of incidents related to the above-listed pharmacist activities. This analysis was made possible by the commitment to quality and safety exemplified by community pharmacy teams across Canada.

METHODOLOGY

Medication incident reports with an outcome of harm that were submitted between January 1, 2022, and June 30, 2024, were extracted from the National Incident Data Repository for Community Pharmacies (NIDR), as well as the Individual Practitioner Reporting (IPR) and Consumer Reporting databases.* Search parameters reflected terms associated with pharmacists’ scope of practice, including “clinical assessment”, “therapeutic substitution”, and some province-specific terms (e.g., names of provincial programs). Reports were screened, and incidents were excluded from the analysis if they involved only historical pharmacist activities or occurred in inpatient settings. The analysis was conducted according to the MIA methodology from the Canadian Incident Analysis Framework.2

QUANTITATIVE FINDINGS

The data extraction returned 595 reports. After application of the screening criteria, 55 reports were available for quantitative and qualitative analysis.†

The majority of reports described mild harm (Figure 1). Although less than half (45%) of reported incidents involved patients younger than 18 years or older than 65 years, these patients accounted for almost all of the incidents associated with moderate or severe harm.

FIGURE 1. Severity of harm reported.

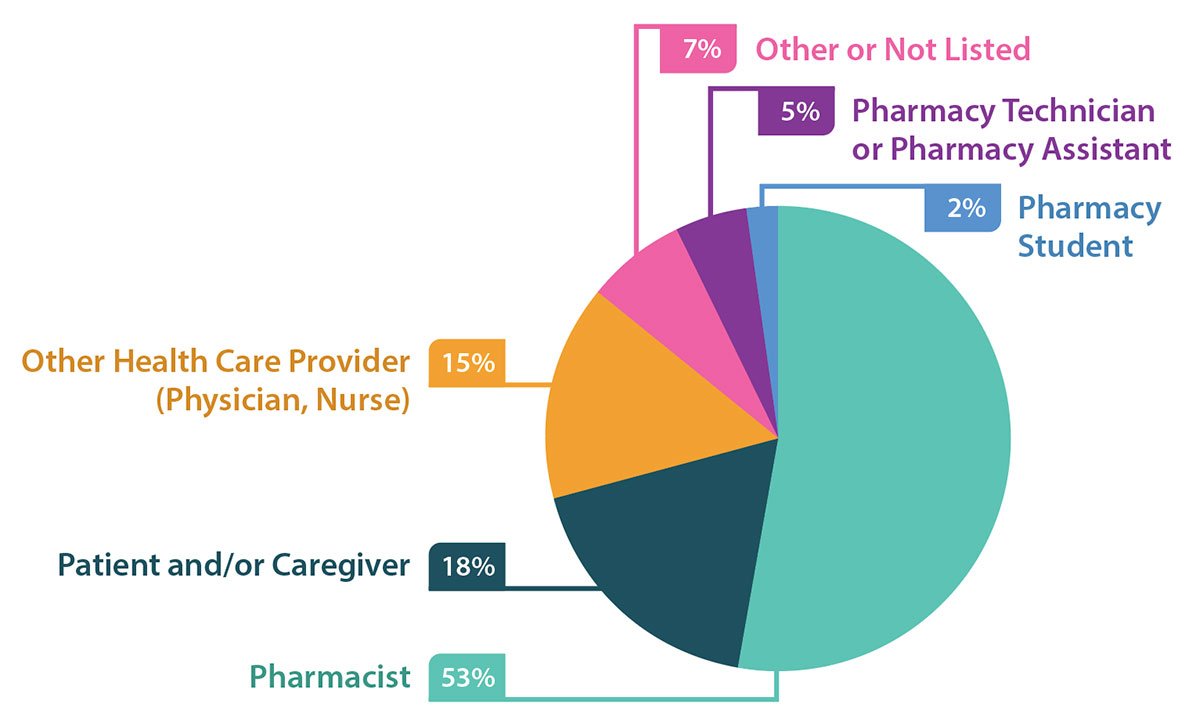

Pharmacists (53%), followed by patients and/or caregivers (18%), were reported to have discovered most of the incidents (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. Discoverer of incidents identified in reports.

QUALITATIVE ANALYSIS

The qualitative analysis generated 2 main themes and several subthemes (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3. Themes and subthemes identified in the multi-incident analysis.

THEME: Vaccinations

Pharmacists in most Canadian jurisdictions are authorized to prescribe and/or administer vaccines for various conditions,5 and the range of permitted vaccines continues to grow. Evidence shows that pharmacists play an active role in increasing vaccination rates.6,7 In the current analysis, contributing factors described in incident reports within this theme included mismanagement of inventory, high workload, and the preparation of multiple vaccines for simultaneous presentation of multiple family members for vaccination.

Subtheme: Vaccine Inventory Management and Reconstitution Practices

Comprehensive vaccine inventory management and reconstitution practices support safe vaccine use. Incidents captured in this subtheme involved use of expired vaccines or omission of the reconstitution step (e.g., not mixing the vaccine with a diluent).

TIPS

- Regularly monitor inventory to identify expired products.8 Promptly remove from stock and clearly identify any expired vaccines for disposal or return (according to provincial regulations).9

- Designate an area that is free of distractions and stocked with all necessary resources (e.g., product monographs, workflow checklist) for reconstituting and preparing vaccines.10,11

Subtheme: Patient Care Processes

Patient care processes encompass screening to ensure appropriate vaccine choice, organization of vaccine-related workflow at the pharmacy, and vaccine administration. Incidents reported within this subtheme included incorrect product (e.g., wrong vaccine) and incorrect dose (e.g., pediatric dose for an adult).

Incident Example: A parent and 2 young children were waiting together in one room to receive influenza and COVID-19 vaccines from the pharmacist. All of the vaccines for this family had been pre-drawn into unlabelled syringes and placed in 2 baskets: one for the influenza vaccines and the other for the COVID-19 vaccines. Within what was described as a “chaotic environment”, which included a crying child, the parent was inadvertently given a pediatric dose meant for one of the children.

TIPS

- Schedule vaccinations with sufficient time and staffing.

- Consider bringing into the room the vaccine(s) for one demographic (e.g., pediatric) at a time to minimize incorrect patient errors.

- Avoid preparing or pre-drawing vaccines for more than one patient at a time. If this is not possible, label each syringe (e.g., with vaccine name, dose/volume,9,11 beyond-use date, and patient name) according to jurisdictional regulations.

- Ask the patient what vaccine they are expecting, then verbally confirm the product name, dose/volume, and indication for the vaccine being administered.10 Show the vaccine label (on either the syringe or the vial) to the patient/caregiver, where feasible.

THEME: Pharmacist Prescribing

Pharmacists’ authority to renew/extend, adapt/adjust, or initiate prescriptions, as well as their authority to order laboratory tests and interpret the results to support medication management, varies across jurisdictions.12 Factors described as contributing to incidents within this theme included inadequate review of a patient’s medication history, incomplete patient medication profile (including improper documentation of discontinued medications), and insufficient discussion with the patient regarding medication changes.

Key Learning:

Conduct a comprehensive review of the patient’s medication and medical history when undertaking a prescribing activity.

Subtheme: Renewal/Extension of Prescription

Prescription renewal is the prescribing activity most widely applied by pharmacists across the country. It supports continuity of care for patients who are unable to obtain prescription refills from the original prescriber. Incidents captured in this subtheme included renewing an incorrect drug (e.g., a discontinued medication) or renewing a correct drug at an incorrect dose.

Incident Example: A pharmacist extended a prescription for divalproex that had been transferred from another pharmacy. The total dose was not confirmed with the patient’s caregiver or the provincial electronic health record (EHR). The patient experienced a seizure and was hospitalized. It was discovered that the renewed prescription was only 1 of the 2 prescriptions needed to achieve the patient’s full dose (i.e., the intended dose consisted of a combination of 2 different tablet strengths).

TIPS

- Conduct a comprehensive review of the medication history with the patient to confirm medications that have been started recently, those that have undergone dose changes, and those that have been stopped.

- Access the patient’s EHR (if available), and communicate with the patient, primary care provider, and others in the patient’s circle of care, where feasible.

- Activate functions within the pharmacy software system designed to make the pharmacist aware of changes inadvertently made (e.g., dose, directions for use) when renewing a prescription.

Subtheme: Therapeutic Adaptation of Prescription

Most jurisdictions allow pharmacists to adapt existing prescriptions and make therapeutic substitutions.1,12 These actions may be informed by laboratory test data, which are accessible to most pharmacists through provincial databases and which, in some jurisdictions, may be ordered by the pharmacist.1,12,13 Patients can benefit from prescription adaptations in several ways, including easier administration (e.g., changing the formulation from a large capsule to an oral liquid formulation), reduction in potential adverse effects (e.g., reducing an antibiotic dose according to a patient’s renal function), and minimized interruption of therapy during drug shortages (e.g., substituting a therapeutically equivalent medication for one that is unavailable).14,15

Incidents included in this subtheme involved incorrect dose/frequency, and drug–disease interactions that were missed during clinical assessment (e.g., a dose that needed to be reduced due to renal impairment).

TIPS

- Integrate routine review of laboratory data into clinical assessment processes to verify, adapt, or modify prescriptions and for comprehensive medication reviews.13

- Continuously update the patient’s profile with relevant clinical information, such as allergies, medical conditions, and renal and/or hepatic impairment (including supporting laboratory data), along with the most recent date of revision, to support appropriate prescription adaptations.3

- Use pharmacy software functions intended to alert the pharmacist to drug–disease interactions (e.g., use of a renally excreted drug in a patient with renal impairment) to prompt potential medication adjustment.

- Communicate any prescription changes to the patient both verbally and in writing, so they know what to expect4 (e.g., different tablet appearance or different directions for use).

Subtheme: Initiation of Prescription

Pharmacists’ authority to initiate a prescription varies across the country.1,12 This activity can be undertaken in all provinces and one territory to treat a specified list of medical conditions, is enabled in most provinces within the context of collaborative agreements, and is permitted in one province for any Schedule 1 drug.16 Incidents within this subtheme included missed drug–disease interactions.

Incident Example: A pharmacist felt pressured, during multiple discussions with a patient, to prescribe an antibiotic for a urinary tract infection. Although prescribing was within the scope of practice, the patient’s complex medical history complicated the treatment. Despite having reservations, the pharmacist prescribed an antibiotic. However, the medication was not appropriate for the patient’s clinical status, and the patient experienced harm.

TIPS

- Access relevant assessment and treatment algorithms to determine when referral to another health care provider may be warranted. Share this decision-making resource with the patient, as needed.

- Add reference data to medication files in pharmacy dispensing software for ready access (e.g., medication dosing according to renal function).

- Implement independent double checks for pharmacist-initiated prescriptions for high-alert medications to minimize the risk of confirmation bias in the verification process. If the pharmacist is working alone, a delayed self-check can be done.3

- Schedule follow-up calls to monitor patients for the effectiveness and safety of medication(s) prescribed by the pharmacist.

CONCLUSION

Community pharmacy teams exemplify their commitment to safety through reporting of incidents and near misses. Shared learning in this bulletin can inform continuous quality improvement to support pharmacists in practising to their full scope, including vaccination and prescribing activities.

![]()

The Canadian Medication Incident Reporting and Prevention System (CMIRPS) is a collaborative pan-Canadian program of Health Canada, the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI), the Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada (ISMP Canada) and Healthcare Excellence Canada (HEC). The goal of CMIRPS is to reduce and prevent harmful medication incidents in Canada.

Funding support provided by Health Canada. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of Health Canada.

The Healthcare Insurance Reciprocal of Canada (HIROC) provides support for the bulletin and is a member owned expert provider of professional and general liability coverage and risk management support.

The Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada (ISMP Canada) is an independent national not-for-profit organization committed to the advancement of medication safety in all healthcare settings. ISMP Canada’s mandate includes analyzing medication incidents, making recommendations for the prevention of harmful medication incidents, and facilitating quality improvement initiatives.

Report Medication Incidents (Including near misses)

Online: ismpcanada.ca/report/

Phone: 1-866-544-7672

ISMP Canada strives to ensure confidentiality and security of information received, and respects the wishes of the reporter as to the level of detail to be included in publications.

Stay Informed

Subscribe to the ISMP Canada Safety Bulletins and Newsletters.

This bulletin shares information about safe medication practices, is noncommercial, and is therefore exempt from Canadian anti-spam legislation.

Contact Us

Email: cmirps@ismpcanada.ca

Phone: 1-866-544-7672

©2025 Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada.